Would you like to identify birds by the sounds they make, but just can't get the hang of it? If so, you might be interested in the visual approach, with sonograms. Here is an introduction to the topic.

|

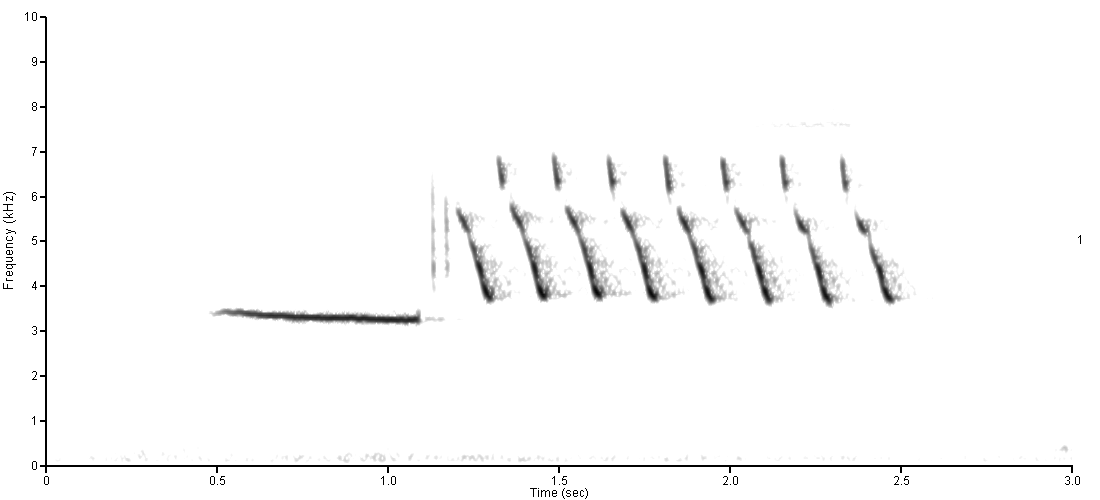

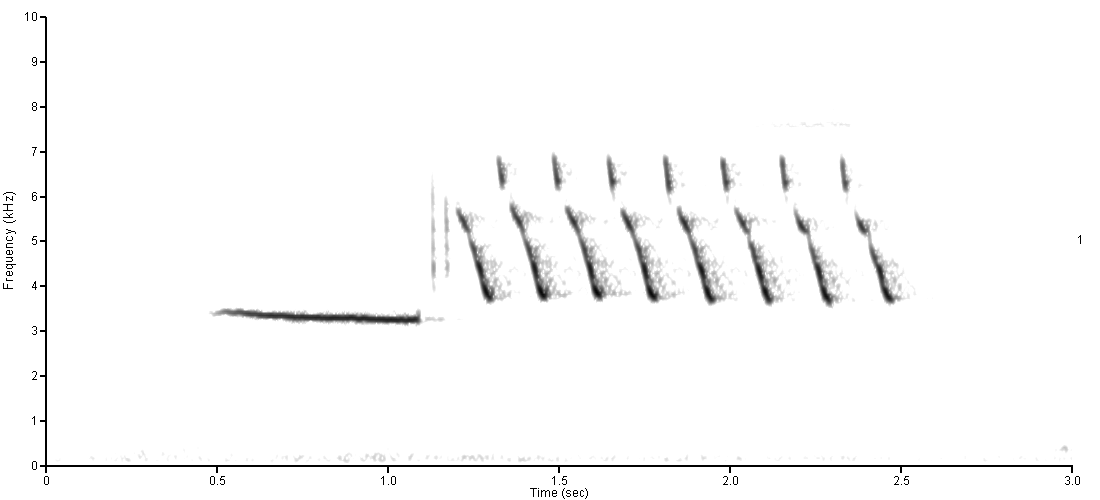

To the right is a picture of a bird song. It is called a sonogram, which is short for "sound spectrogram." It displays pitch on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis, rather like a musical score.

It's beautiful in its own right, isn't it? But it is also a reminder of a sound, a sound that once pulsed through a pine forest in the South Carolina Lowcountry. Although that sound is gone forever, a replica of it resides on my computer, and on a server somewhere that connects me to you. As soon as you click the sonogram the sound will be awakened for you to hear.

But first, do you already know what bird made it? If not, read on.

|

|

You can play the sound again and again. Notice the long pure note depicted by the flat line from 0.5 to 1.0 seconds on the horizontal axis. It is easy to see that the flatness of the line represents uniformity of pitch. Let's call that pure tone a "whistle."

The second half of the song is a "slow trill," slow enough that you can count each repeated phrase, a trill because it is a series of repeated short phrases. The sonogram shows us that each phrase is a slur, a sweep from a high to a low frequency, but we don't really hear that. Each phrase just sounds like a "chirp" or even a "click."

After listening, did you recognize the song? The basic pattern of a whistle followed by a trill is used by a number of bird species worldwide. The two main practitioners of this pattern in the southeastern US are the Eastern Towhee and the Bachman's Sparrow. Which one is it? If you are in doubt, click here for another clue. This cut takes over a minute to play.

* * *

Why did we have to listen to a whole minute of singing? Because there is additional information about the species of the singer in the sequence of songs he sings. If each succeeding song is different from the previous one, bird musicologists call that "immediate variety." Bachman's Sparrows usually sing with immediate variety, while Eastern Towhees usually sing with "eventual variety," that is, they repeat the same "song-type" a number of times before switching to another variant. The many song-types of Bachman's Sparrow do differ consistently from the many song-types of the Eastern Towhee, but if you're not sure which you're listening to, noting the repetitiveness of the singer (serenade syntax) can help you nail the identification.

* * *

Click the link above again to see if you can detect transitions from one song-type to another. Is variety immediate? If it's hard to keep up with what you've already heard, try listening while looking at the moving sonogram below, courtesy of eBird.

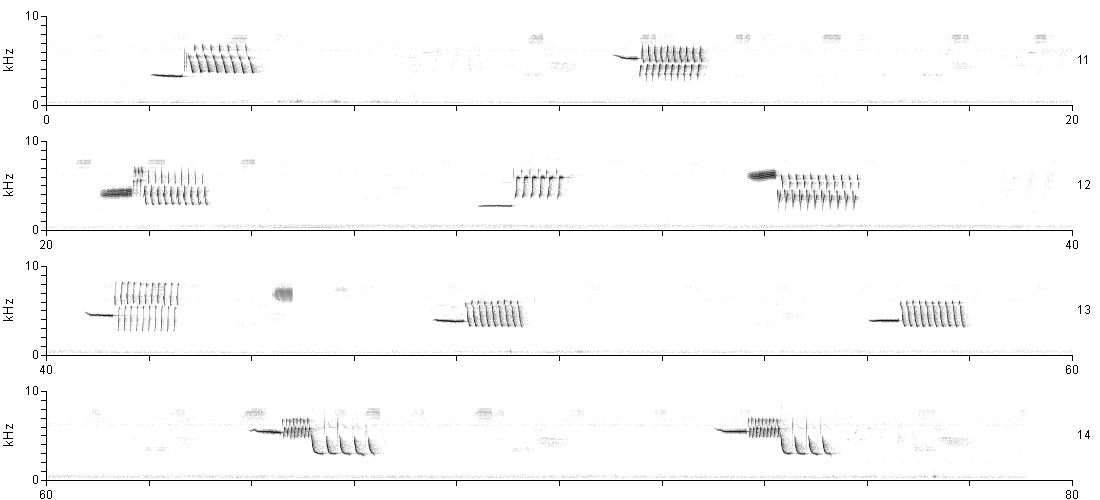

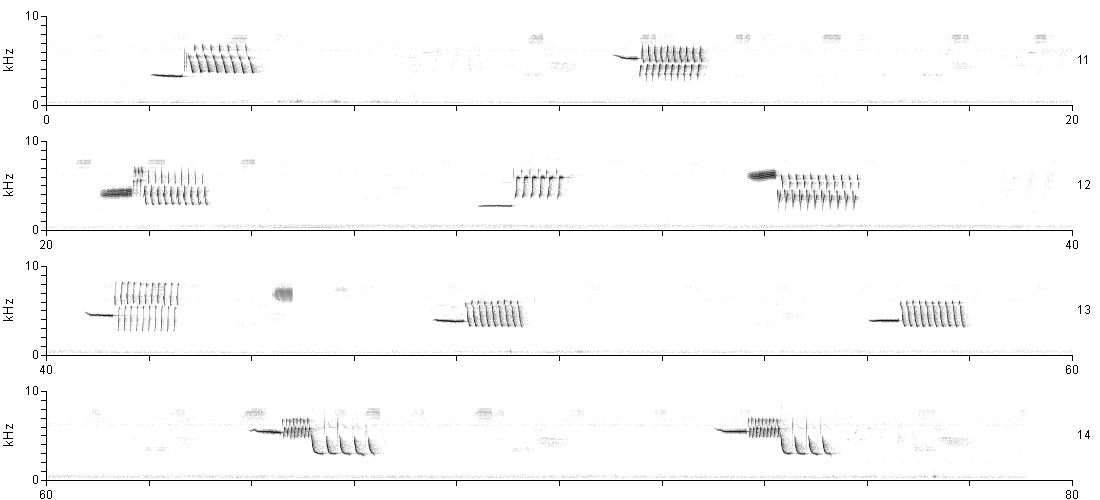

Now, that's all well and good, but one of the wonderful things about sonograms is that they can be used to freeze time. The sound of interest occurred in the past, yet we still have access to it. Just as a page in a book is the freezing in time of a speaking voice, a sonogram can be used to lay out in space a temporal sequence of sounds. That's just what a musical score does. So, take a look below at the entire sequence of songs in our Bachman's serenade, frozen in time, so we can examine it at our leisure. Look for patterns in this "score." And you can listen, too, by clicking it. It won't move, but you can follow the sequence of sounds on the score with your finger.

Eighty seconds of singing by a Bachman's Sparrow. Each of the four sonograms depicts a 20-second segment of the serenade. Clicking anywhere in the figure will play the entire 80 seconds, with controls at the top of the page.

|

Patterns I notice:

1. All the songs are similar: a long whistle is followed by a trill.

2. But, there is variety. The first seven songs are all noticeably different from each other.

3. The whistle-types and the trill-types are independent. Wood Thrushes also do this.

4. Succeeding whistles seem to differ dramatically in pitch. Hermit Thruses also do this.

5. We probably haven't seen all of this male's repertoire, as there was only one occurrence of each song-type. (The two tandem repeats are not independent occurrences.)

|

All these interesting observations, which are accurate descriptions of the evolved communication system of the Bachman's Sparrow, are accessible to us because of Sonograms. So, how can we use them to learn to identify bird songs?

TO LEARN MORE

Invite me to give a talk at your Audubon chapter or nature club. Just email web at archmccallum.com.

The following two books use sonograms extensively:

Nathan Pieplow has recently published the Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America, and ditto for Western North America. They are tours de force of scholarship and together the best single-source comparison of the bird sounds of Canada and the U.S. ever published.

Don Kroodsma distilled his decades of academic research into a highly readable account of the many ways birds use sound to communicate in The Singing Life of Birds, winner of the John Burroughs Medal and many other awards.

I published two articles in Birding magazine on the uses of sonograms:

PDF of Birding by Ear, Visually, Part 1: Birding Acoustics

PDF of

Birding by Ear, Visually, Part 2: Syntax

As part of the article on syntax for Birding (see above), I created three prototype spreads for a "field guide" to sonograms. You can review them by clicking the links below. Clicking on a sonogram will play the specific sound under the cursor. The Empidonax page, for example, is linked to 30 separate sound clips.

A similar page for eastern Empids has just been completed. Follow the link below to visit it.